AN OFF-THE-RADAR ICON

Questions for George Hildrew

Elwood Beach

I caught up with the painter, George Hildrew, in his Brooklyn, New York studio. Hildrew is a bit of an iconic character, that is certain. A bit of the Ned Kelly/Jesse James type. An outlaw without the violence. After a couple of glasses of calvados we got on with it. And the hours, which turned into days, were distilled into what follows.

|

|

[virtual tour / music by Mars]

|

Elwood Beach: You once mentioned, perhaps it was at your 2006 talk at the Black Mountain College Museum in North Carolina, that you didn’t want to be labeled either an figurative or an abstract painter. What’s the rub?

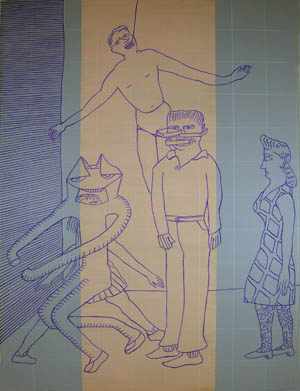

George Hildrew: I prefer to exist in the crossfire. I want options not reins. Both labels suggest a bunch of tired formulas. I want to exist in the idea. When the idea is out there I feel exalted. I like that feeling. When it looks like art, watch out. I like the eccentricities of everyday life. I like to exist in the copy. I like the procedure, messy or clean-cut: A progression of reveries, of ideas popped from the cultural mix that create the stories we tell ourselves in our heads.

EB: You were shaped by the 1940s and 1950s growing up as a Jersey boy in the suburbs of Camden and Philadelphia. How did this prepare you for things to come?

GH: I grew up in the suburbs—Haddon Heights, New Jersey. My father operated an automobile upholstery and glass business in nearby Camden from the 1940s through the 1970s. He was a totally charismatic, literate and eccentric character, a great social observer and commentator. In the 1950s, during the cold war, he studied Russian privately, in Philadelphia, with a Dr. Federoff. I, simultaneously, studied Polish (my mother’s parents were Polish) with Federoff’s aunt, Junia Anrep, who was a delight. I was in 3rd grade at the time. The Polish was a disaster with no one to converse with in the Waspy Burbs. But Anrep gave me a sense of what European-Russian intellectual cultured experience was like. I felt I had entered a dream space in her dark, tapestried Russian interior in the Powelton Village section of Philadelphia—taking walks past urban gardens and watering the flowers in her own sequestered, walled-in, space. Oddly enough, I recently was startled when coming across a book on mosaics where it referred to her ex-husband, a mosaic artist in London in the early 20th century. I remember Anrep talking of him and their trip to Pompeii after fleeing Russia during the Revolution. Anyway, these early experiences gave me a taste for urban life.

EB: Early on you were drawn to theater and acting, yet you chose Philadelphia College of Art (The University of the Arts) to begin training as a painter. How come?

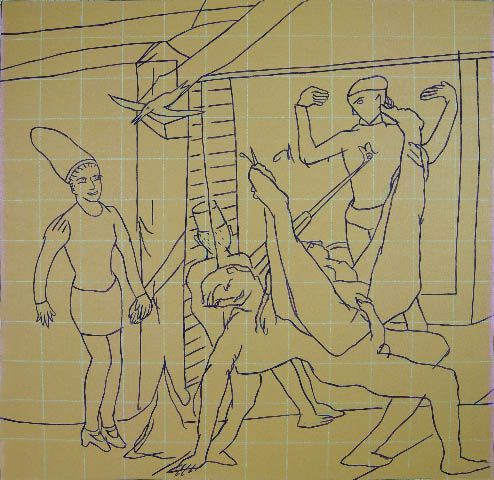

GH: I was drawn to the theatrical probably through an appreciation of my father’s dramatic persona. He was an orator for any occasion—Lions Club, church functions, Ukrainian picnics—you name it, he gave the introduction, the explication, the toast. I remember my own early performance—age 12—speaking as an amateur ornithologist on prehistoric birds to the Lions Club. Like my father I collected my own circle of intense eccentric individuals; mine were the bird-watchers of the local Audubon Society. I would accompany them in animistic forays into the spring woods on Sunday mornings so as to avoid church, having exhausted my initial fascination with the religious parables and stories that populated my earliest Sundays. Also, about the same time—7th grade—I had a wonderful young art teacher by the name of Pat Quinn who was a recent graduate of the Philadelphia College of Art. She had a hot red MG convertible and drove me into Philly to the Beatnik coffee shops and craft stores. I loved it—out of Suburbia. She also, quite by accident, met my mother’s youngest brother on a skiing trip. She was also dating my boy scout troop leader—me a boy scout, go figure. She told me one day she had to usher my uncle out the back door as the scoutmaster was coming in the front one. Hilarious. She took the class on a tour of the Philadelphia College of Art and I was mesmerized. I wanted to go there after that. Still, in high school, I helped out in painting stage sets and got into acting. I remember delivering this delusional monologue of a serial killer who murdered his sisters, in a play called “Uncle Harry” which, I think, was originally a movie—“The Strange Affair with Uncle Harry,” with George Sanders. It was an out-of-the-body moment in that one scene, that one night. It certainly opened my eyes, quite by accident, as to what the acting “high” is. One summer after that I took acting lessons at Temple University. But I found acting too collaborative. I needed more privacy and control, so I picked painting. That said, my painting is highly theatrical. Oh yes, the genes. My father had relatives who were dancers on the vaudeville stage in England.

EB: You’ve been married to a couple of babes and have always been attracted to strong, outspoken women. What do you think this is about?

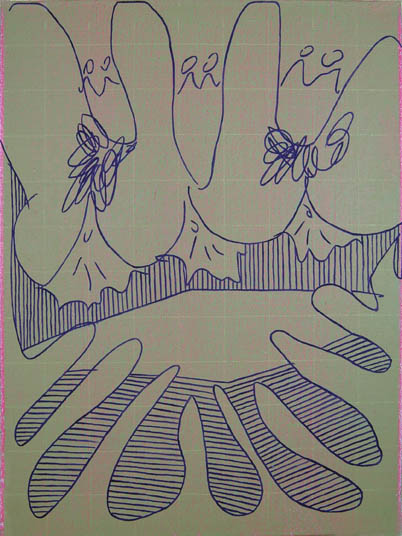

GH: I love Dr. Freud. The wives—“Yes, what would Dr. Freud think?” “Yes, outspoken.” There is a bit of my father in all of it. He was so outspoken. I know that. I like that. I’m accustomed to it. I’m more voyeuristic, like my mother. She liked to watch the action as I do. Every exhibitionist needs a voyeur. I’m an astrological Libra, like my mother—once in a while we need a full throttle opposite to pull us off our balance. The wives and girlfriends seem like some kind of parental reenactment, at least in part. Thank you Dr. Freud. My first wife was an anthropologist and shared with me her interest in cultural anthropology and the experience of other ways of being, which was part of the 1960s mix. I did a lot of reading in that area which still fuels my interest in foreign travel. I like to enter that different mental space. As regards to my now darling wife, Judith, she’s a muse of a different sort. Being a nanny, she shares, and has awakened in me, the significance and importance of play. The enrichment of life and art, through the development of the imaginative faculty in children, is

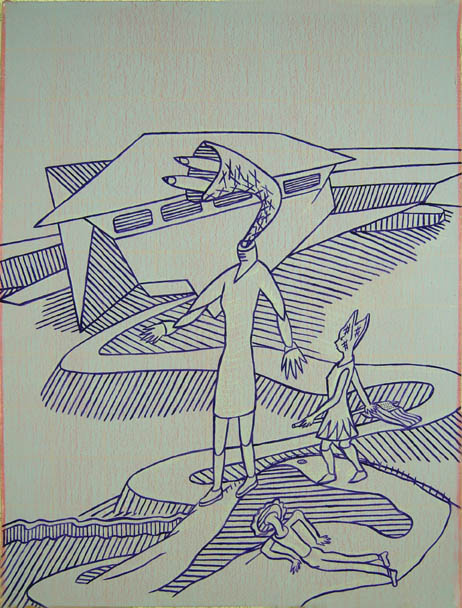

something she feels is very important. She has brought this into my life. Certainly, the figural paintings from the last 8 or 9 years are somehow connected to our conjoined wave lengths and our ability to act out fictive invented worlds.

EB: You had an early infatuation with art that was slightly off scene, mannered. That seemed to be the ticket for some of your own justifications. Would you elaborate?

GH: In 1968–69 I had a Fulbright-Hays Fellowship to Italy to examine Mannerist painting. This was the result of an interest developed in graduate school at Indiana University. I felt an infinity, then, with the Mannerist aesthetic position with its tug-of-war against the worn out Renaissance tropes. I liked more off-the-radar artists such as Beccafumi and Mabuse. I felt being an artist interested in narrative structures—figural tropes of form and abstract spatial structures—I was in a similar relationship to Modernism as the Mannerists were to the Renaissance style. There seemed to be a parallel set of don’ts that they had which echoed Ad Reinhardt’s set for the 20th century. Still, just as beautiful as a monochrome was in that period of High Minimalism, it wasn’t enough for me; just as the seemlessly idealized form, perfectly integrated in space, wasn’t enough for the Mannerists. In fact, they seemed like the same thing. Still, once I got to Italy, the Mannerist spell dissipated and, when I returned to the States, what I disliked about the Renaissance did exert a pull. I think it was the wholeness to the vision. But today, again, I’m more wary of it. In the 1980s I said don’t edit—just do every stupid idea that passes through your head. I felt trapped by the integrated surface. I still feel a lot that way but, in the end, it’s all belief and being fully attached to the idea as it’s going through your head, on to the canvas.

EB: The 1980s did seem to bring out your playfulness, not only in your work, but in your escapades in and out of the New York scene. You and the painter, Thomas Trosch, seemed to have spent a lot of time role playing, crashing parties and gallery openings and being both exhibitionists and voyeurs. What was that all about?

GH: A sense of humour. Acting out. Being in the studio cave too long. Don’t edit your own absurdity, especially in the face of the absurdity of others. Be complicit.

EB: And what did the 1990s bring you?

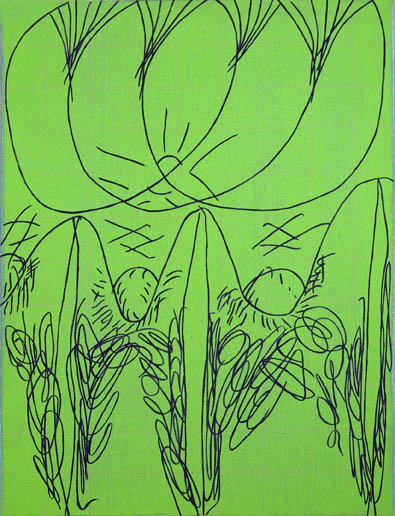

GH: By the 90s, New York seemed much less fun. It had lost its intimacy. The careerism and commodification, which seemed absurd fun in the 80s, became a gargantuan rote machine. I lost interest. By the end of the 80s my work, which had become figural, became abstract, and by the 90s I was a process procedural abstract painter. This had partly to do with a do-the-other-thing mentality or do-anything-everything mentality. But probably more than that, it had to do with a workshop experience I had in scenery painting for the theater. This gave me a procedural view of painting that distanced itself from judgment and sensation. It was a big breakthrough, getting rid of tickled nuance.

EB: Branding, Careerism and Commodification is at a fever pitch today. It was, as you mentioned, already there as you slid into the scene. Has this influenced you in any way or has it only, perhaps, bemused you? Perhaps it has squashed a bit of your idealism.

GH: Branding, Careerism and Commodification—yes, it was all there when I came out of my hermitage in the 1980s. But it was present even if I was too young to recognize it with Castellis of the 1960s, when I was beginning my observationship. In fact, the old regionalist painter, Clyde Singer, once said—“Oh, there were Mary Boones in the 1930s. They were always there, probably in the caves, branding the animals. And we were there, too, trying to get a good spot on the wall: And who would want it any other way?” I am bemused by practically everything, so why not, and as for squashed idealism, I remember writing a paper in college on pragmatism. Although, today, I feel more neo-platonically oriented, so that’s idealism. Yes. the continuum.

EB: When did artists become so complicit to all of this? And is it entropic?

GH: Artists can either whistle in the dark or join the fray in our capitalistic consumer culture. Neither is too appealing.

EB: The well known metalsmith, Daniel Jocz, who is a good friend of yours, said you are the perfect example of a contemporary anarchist. Are you?

GH: My anarchy is totally personal and manifests itself in the art. My father, as a role model, presented personal anarchy as a valuable way of wrestling with the complacency of suburban social culture. It’s an anarchy to the squelching of thought and possibility—an anarchy that is constantly setting limits on itself. Who wants to mouth received ideas? Who wants anarchy, after all, that’s just anarchistic? Anarchy to what effect? Anarchy for a better world—a better art? What would be better? Or the point? There is always anarchy working on all kinds of levels. And there always needs to be a challenge to the status quo. It’s less fraught with consequences in art—so more pointless. You need to show what no one wants to hear. Yes, I remember curator-gallerist, Tricia Collins, in the 80s saying Trosch and I “broke all the rules.” Those rules to which she referred, I do not know—aesthetic or careeristic, with regard to our gallery “etiquette?” Then there was Wolfgang Staehle reprimanding Trosch and myself for our smirking, laughing, good humour when faced with the careeristic decorum of a Daniel Newburg Gallery opening. So, yes, I can be naughty—anarchistic. It can be life-enhancing. I love clichés and corny Freudian and Jungian psychology. And all sorts of dated maxims and proverbs and cultural platitudes. I love participating in them and I love sending them up. I love the cultural complexity of agreeing with them without irony. Now, I say, approach the painting from where you have the greatest psychological friction or resistance. If I hate Minimalism, I do it. If I hate control, I exercise it. If I hate cartoons, I use them. If I find Surrealism corny, I adopt it. If I hate the sublime, I investigate it. Just say “yes” and the resistance loosens its hold, so you have to find a new annoyance to agree with. There are so many things to dislike but in the end they are all so adorable. So just say “yes” to something else you find grating. I really must do media installation art. In the end I’ll find it uber adorable.

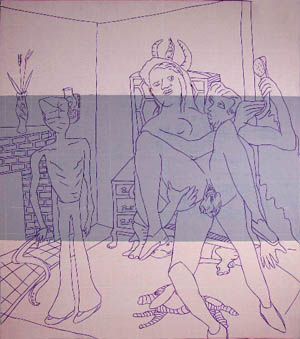

EB: I came across something that was written about your work indicating that your characters attempt to perform some sort of social satire but do not understand their implications or their results. How do you compare this to, say, the characters in a Balthus or a Paul Georges painting? Or perhaps, more contemporary, the narratives of Dana Schutz or Trosch.

GH: I am the social satire, as I’ve said. Yes, I am rather impervious to implications or results...so much the worse for me, I suppose, but who cares. Yes—the paintings are a mirror, and a mirror of a mirror. You gotta love that Plotinus! My characters seem oblivious and uncomprehending. Is this character assassination? Anyway, which Balthus, Georges, Schutz or Trosch? Perhaps Balthus’s 1933 show was oblivious and uncomprehending of implications and results. Georges always seems more baroquely

vigorous, sensuous and inclusive. As to Schutz, I was taken with her huge Bedlam-like hospital ward with shark or whatever. It did seem to express the vast incomprehensible absurdity of contemporary life. As to Trosch’s work, there is a wonderful farcical absurdism expressed with a gleeful childish mud-pie abandon—an arena unapproachable in contemporary figuration—a total lack of taking any aspect of the whole thing at all seriously.

EB: I understand that you have an uncanny intuitive sense of things to come, the restless ability to predict. Perhaps it’s connected to your anarchistic tendencies. How developed is this paranormal gene and how has it informed your work?

GH: Oh, yes, my paranormal capacities. Well, as Judith, my wife, says—“So why haven’t you won the lottery?” I think it has more to do with neo-platonism than anarchy. It’s the English eccentric paranormal gene from my father’s side of the family. He was into mysticism and spiritualism, as well. I don’t know, it’s about some kind of telepathic interconnectivity. I do a lot of reading on outmoded religions—Mithraism, Paganism, Gnosticism. I remember talking on the phone in the 80s with the artist, Frances Hynes. We hadn’t spoken for 8 or 10 years, since an exhibition with Elie Poindexter Gallery in the 70s. After hanging up I went from my Brooklyn studio to Manhattan. As I was changing trains at 57th Street, Frances appeared at the train door. One of many like

occurrences. Why, this drawing of people to me? It is totally subliminal and can’t be willed. In fact, a similar occurrence happened yesterday. As to the paranormal gene informing the work...it seems that, at this point in the painting enterprise, I am able to telepathically visualize from the past to the present on to the fictional space of the painting surface. Maybe it’s years of painting that has made me telepathically sensitive in everyday life. But I know in order to paint, I am connected to what I paint.

home