Framing & Accumulations: An Interview with Shelton Walsmith

by Mathias Svalina

(photos by John Pack)

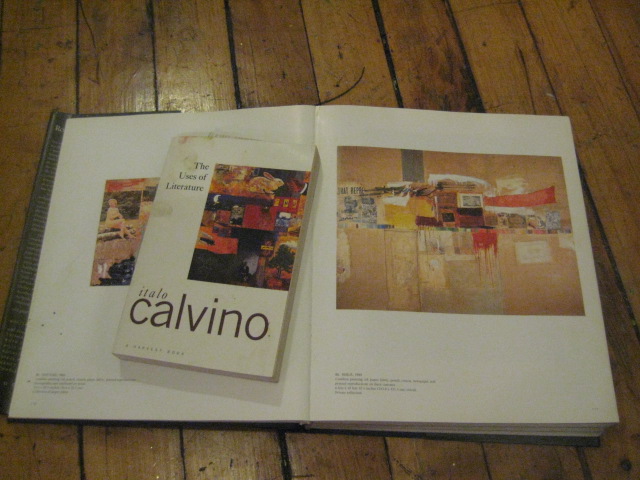

Shelton Walsmith is an artist from Texas who works from Brooklyn, New York. His paintings, photographs and drawings have been widely collected and have been used for book covers from many presses, including the series of Italo Calvino books published by Harvest Books in the late 90s and numerous issue of The Paris Review.

I love his work. I find it playful and haunting in unfamiliar ways, while also negotiating the Western tradition of aesthetic beauty. He is one of my favorite painters but also one of my favorite people to talk to. He is opinionated and associative and his love for the presence in the world comes through in everything he does. A talk with him becomes something between an art history lecture and a Southern front-porch storytelling session.

For this interview I visited his studio in Park Slope and I asked him to discuss the work and thinking that goes into some of his paintings.

You can visit his website for more images of his work or to contact him: www.sheltonwalsmith.com

Mathias Svalina: Tell me about this painting.

Shelton Walsmith: This one here? It’s interesting, this one woman came through & she bought a piece, a piece that no one had ever mentioned, that no one ever said they liked. And then she said that she wanted me to paint a poppy for her. And I told her I don’t paint flowers, it’s not my thing.

I told her that she had a painting in mind that I’d never be able to paint & she said Oh you’re so good with color I want to see you do a big poppy. But I just cannot match what she was thinking, no one would be able to. It sounded like Georgia OKeefe & it’s just not what I do. She told me when you do paint it I’ll pay you for it.

So I painted this one here & I didn’t have any reference & she didn’t want it. Then I painted another one that sold to someone else.

M: You’re going to have a whole poppy series because of this one woman.

S: They are really bad, just awful. This one here looks like a salvation army painting. But the challenge then is that if I can’t make it better it just gets painted out. I never put a canvas in the trash. It’s going to have a long life being different things.

After doing this & being frustrated & wanting to make the sale I was reading in a Picasso biography where he was in a long period of poverty & he was forced to paint flowers for money. This was in 1906. And he literally made ten or fifteen dollars per painting. So he resented that. He didn’t like painting them. It wasn’t his thing, though he is a great still-life painter. He didn’t like flowers at all.

Later on in life when he was fabulously wealthy & had long lines of adulating fans coming to his studio they would bring him flowers & he hated flowers. He was such a dick. In front of the person he’d say put them in a vase without water. And then he’d keep the dead flowers.

And so my poppy paintings are just awful & I hate them & that comes through in the work. And these paintings keep getting worse.

I’m still happy to be on the outside of the mystery of this.

I have this painting here that I’ve been working on. It has a notion of a sacred fire, I’ve been framing & reframing this. It’s really like a daily quest for me: does it have it or does it not. There’s a lot of painting that goes on in your head. Working on it has felt like a lot of going through the motions. But when I’m in the studio & I see it I’m like there it is again. It’s like making another jazz record & on to more jazz, but then sometimes you find what you’re after. Like, there the burning torch.

M: What kind of process do you have in moving from one work to the next. You don’t have a complete idea you want to replicate on the canvas. How do you characterize the thing when you see it?

S: I think it can be best described in that you should be able to look at a painting & it should have light in its eyes. Like when performance artists or conceptual artists are working with process & anything that comes out of that is a relic. So the relic in its doorjamb definition is a lifeless thing. The relic is the locust shell. Evidence that there was something there, rather than the animated thing giving it spirit.

You make paintings & you write poems & you end up with big stacks of things. It’s evidence that you’ve been working, definitely. It’s physical evidence, but then when you go back through any group of things you know the ones that have the light in their eyes. A hierarchy develops & some of them are more alive than others.

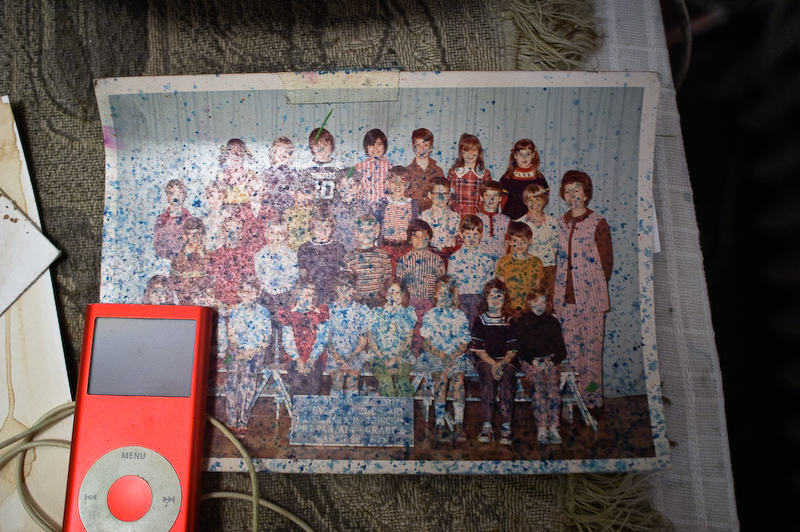

Like the painting of the group of kids—I’ll keep painting on it because the process is still there. It’s still being made. Rather than something that is sealed off. I think that’s the deal with the unfinished Turners as well—you get to see the skeleton rather than the heavily costumed character. You get to see all the way through the thing. The Cézannes also, the unfinished parts of the canvas drives me & a lot of other art lovers crazy because that’s peeking behind the curtain. Seeing that little pencil that isn’t filled in, that’s where the painting is still alive. You see the pears or apples that are beautifully finished & then you see that raw linen & that’s where the dress is open.

M: Is that an appeal aesthetically or craft-wise?

S: Without being a painter I think I wouldn’t be as aware of it but I’d still love it. There’s the raw canvas left there & that’s exciting & pretty & we think about a stripped down version of a song & how you are more suddenly aware of the melody. You’ve known it all along & appreciated the orchestration & you realize what you love so much about it.

M: That reminds me of this version of Billy Strayhorn singing “Lush Life” himself. Obviously recorded on cheap equipment at a nightclub & he has a pretty awful voice. It’s such a familiar song that you hear more of it in the way he misses the notes. It becomes a sad, darkly ironic version when filtered through his life. He is unable to sing his own romantic song, both in that he doesn’t have the voice for it but that he also doesn’t have the life for it.

So if this [painting to the right] is the armored costumed construct for you, where does this begin for you?

S: See down here at the bottom where it’s just paint? Lots of paint there. It’s concerned with paint for the sake of gesture & the pasty quality of the thickness. It superficial in its focus on surface, because the work has to be painting, good painting before it begins to describe anything. You should love the paint.

I think that sweep down there is that. It’s not where that painting started.

M: Do you start with an idea?

S: It began as a response to the tapestry. To me the tapestry, before it's anything else is a field of color & the strength of it is that it’s tone against tone. One tone butting & making itself different from the other thing. And it never coheres into description.

M: Almost all the colors in the tapestry reflect in the paint.

S: Yeah, it’s not matching like how you’d match a mat to a poster. It is like these colors & things freed from their constraints & operating just as color. You see this sweep here? I’m having a problem with it right now. I’m doing that strong gaze thing that makes me want to do something to it & I have a brush in my hands.

M: Is that how you think about your paintings?

S: Yeah, if something is unfinished that means more painting & that’s good. But if the job is done then that’s like a romance that has seen its course.

M: Do you get the desire to call her up years later?

S: You shouldn’t. It’s always a bad idea. Unless you’re going to paint it out. Retouching is a bad idea. But knocking it all out & starting all over is ok. Because there is a difference between accumulations & collections of things. An accumulation I can’t stand is in that doorway over there of canvases that are just stacked. Like stuff in the attic. I can’t stand those things. The paintings should be so good that you can’t store them. So that they have to be out.

Which is why I’m running out of space & I’m constantly shuffling my canvases around. It’s because I really don’t want one to be behind something for long. That painting just behind you, I still have all my feelings for that piece. My feelings are all still in place. And it’s older, it’s getting to be eight years old. It’s at risk of being damaged. It needs to be up & gloriously framed. Treated the way I felt about it the day I finished it. But that’s impossible.

I don’t want accumulations, but I’m always proliferating & creating accumulations.

M: But you contrast accumulations against collections. Do you see this canvas as a collection.

S: Yes, not a collection of things, but a collection of tendencies. I’m trying to marry these shapes, these rectangles & then I have this cut-out relief. It’s drilled into the painting. Like windows through the painting.

It’s like reframing, that landscape up there it’s pretty much a drawn painting. But we as people bring right angles to the landscape. The right angle doesn’t happen, but we need to reframe for our own systems. That’s what we do, we’re more comfortable looking at the landscape through a window than looking at the landscape.

That becomes interesting in John Ford’s westerns. In The Searchers Ford is looking at the landscape. He’s always reframing it so that not only are you looking out the windows down across the porch as people are riding up he’s civilizing the landscape. That's what people brought to the west, especially in his film you’re able to get that sense of that girdle people harness onto nature in order to have it. To not be controlled by it.

And as a painter you’re going to set up a square or rectangle & put nature inside it. Even like Turner, something as wild & ecstatic as Turner is still arrested at the edges of the canvas. So it seems important to have that vocabulary inside the paintings as well as a set of frames.

Also, I know it’s not popular at all, but I love antique frames. If I had my way everything would have big, gorgeous, European-style frames. I would love to bring that kind of art history back with the frame. The contemporary sensibility is to have no frame. We keep framing everything, you know?

I sold these paintings to a very wealthy Arabic woman. It was a big painting & she had me deliver the painting to her place on 6th Ave. So she buys it, doesn’t blink at the price & my nephew is in town the day I have to bring it to her & just as we get there after we’ve carted the painting on the subway, she stops me & says I do want to buy this painting but my brother is here & he’s the head of the family & needs to approve the purchase.

Now, it’s like a whole different deal. And my nephew is this hippie kid from Austin with long dreadlocks & we enter this gorgeous, wealthy apartment & suddenly we feel unbathed.

The brother is this beautiful man, looks like Omar Sharif. Carved features, goatee, elegant dress & he’s being served kippers or some sort of sausage by a woman in an outfit. Very, very wealthy. They have Indian artifacts & such all over the place. And the sweat is pouring out from under my arms because I thought this was a done deal & I was going to pick up the check. And everyone is being so serious & she says to her brother These are the painting I was thinking about buying, what do you think?

The painting was call "Beers, Boats & Boots". Stupid painting, really bad. It had little images of boots & boats on it, all sorts of B things. I think there might have been a bong in it. Just alliterative things. It’s questionable, dubious even to me.

He looks at it very serious. No sense of humor. And he says to me Now tell me Shelton, would you frame a painting like this? And I took a moment & mustered up all my courage & said You know what? Yes I would. And if I had your money, once I had framed the painting I would take another frame & frame it again.

He said Very good, if I decide to do that I’ll call you & you can help me do that.

But it’s true! I would!

It’s really just about me wanting that validation that it really is art.

M: But it’s also an antique, like the old photographs & the tapestry. And the art object doesn’t make meaning aesthetically, the art object is an idea about the object.

S: Yeah, another reframing. Like your children’s games [a series of writings I’ve done that are in the form of instructions for children’s games] That’s the kind of old-style decorative cartouche. The kids are definitely in antique costumes, Dick & Jane or whatever. That’s the intonality you’ve brought in before you started making the art. It’s like “Once upon a time.” I’m there. What do you got for me?

M: Or “In the beginning”.

S: Exactly, I’m there because I know I will be treated to something that will be full of mystery. And again, it’s superficial, it has a lot to do with the surface. But for me, the door closes behind the viewer there. They are inside. They know I’m not playing any games, this is not going to not be art. It’s only art. It’s not going to be real at all, this is going to be like museum art. The flickering cinema is what I want.

It is all artificial. Congratulations, it’s vacation.

There’s this silly feud between Matisse & Picasso. Matisse said a painting should be like an armchair, Picasso said no a good painting should be like a razor blade that lacerates your fingers when you try to touch it. That’s how diametrically opposed they are.

But for me on one day its Anselm Kiefer & you have to crawl across the broken glass to get to the bookshelves. And other time it’s Francis Bacon, in which it’s so pretty who cares about the image. It’s so good. It’s all artificial.

Like after Giles [his son] & I read Old Yeller. We wanted something of that flavor so we turned to Steinbeck & read The Red Pony. And while it’s real, it’s not real.

Like Christo. It’s real, right? He is really taking the landscape & dressing it. And to make it happen & what’s so beautiful is those images he makes. But even those, though, he brings the real in: the fabrics, the collage. He shows you what it’s going to be. And in the end it is the real thing. He doesn’t scale it down to be manageable. Often times when we make things it is necessary for us to have it fit into a book. Like I can’t make the real thing. I can’t put you on a canvas. And I want to fake it. I want to exaggerate.

Creation is playing god a little bit. I’m going to set out to do the first thing. I’m going to create, not just my own little fetishy thing, I’m going to create the whole thing for you.

When something is unfinished it has so much potential. At any moment it could be everything my heart desires.

M: Do you use particular techniques to get to that place for you?

S: Definitely with the silly, splashy paintings. I consider my paintings to be very antique. Mired in a kind of 40s & 50s & 19th century painting. Definitely post WWII abstraction with lots of drips. That’s painting to me. That’s one of the codes—it needs to be viscous. You need to use the paint first. Your fidelity to the paint.

Like who is your absolute hero in poetry?

M: Right now, probably two guys for different reasons. One is Louis Zukofsky. He’s a poet who can be minimalist in his technique & often impenetrable, but deeply involved with literary history to the point where his work becomes an assemblage of gestures from poetic history & political history. Tendencies, as you said earlier. I see him as an intellectual model. He’s rarely beautiful in a liquidity of sound or effervescence of image, but his work always makes me think more about how language makes itself & why poetry is useful. That it presents a form of discourse that no other writing can get at.

But then there’s this guy Larry Levis, who is pretty much the reason I write poems. He’s a smart poet, who’s work has been described as long jazz riffs of what a mind does with an idea. He has this poem, a section of a poem, called “Swirl & Vortex.” In it he writes about the Caravaggio painting of David holding Goliath’s head & David looks like his friend from high school who was killed in Vietnam. And his poem is really a series of ways of thinking about these connections. And that’s a model for his work, placing the individual experience into a system of associations & their histories. The personal experience becomes a nexus point. He’s the guy I turn to when I want that Romantic feeling of being more present in the world, whereas Zukofsky makes me want to do more as a poet.

S: Do you find them present when you’re writing?

M: I’m not sure. Influence is such a constantly evolving idea. When I was a kid interviewing bands or writing reviews I saw influence as just who the band sounded similar to. But the poets who are the most influential to me are not the ones that my writing is similar to.

A critic will see influence by connecting the techniques from one painter to another & that’s how art history will build its version of the aesthetic conversation. But I don’t think you saw someone use a tapestry in a work & then decided to use a tapestry.

But the best writers are ones who do things that no one should be influenced by in this way. I don’t think anyone should be influenced by Hopkins in this way. The best poets are ones who have created such a precarious aesthetic. Like Larry Levis is incredibly sentimental to the point that noon could imitate that & pull it off.

So it’s important to me that my writing responds to people whom I don’t sound like. Cole Swensen or Levis or Zukofsky.

S: Like what Eliot said & Elvis Costello said better, that good poets steal, bad poets imitate. I think that’s true to the extent that you’re in the idiom already. It’s going to come out in different ways. But someone who is conscious about building their own voice knows that’s going to be the center of everything they do & might absolutely lift passages if necessary to bolster that.

M: You’re saying that the use of paint on these canvases signals to the viewer where the painting comes from. That the aesthetics create an initial rhetoric about the world that you live in as a painter. Like a formalist poet will immediately signal to the reader through the received form that there is an idea of poetry that is going on here & they’ll be working inside that. It establishes the playing field.

S: I feel like it’s very difficult to get the heroes to leave the room. Maybe that’s a way that representation is different. I can recognize that things have been done, but when I’m in John Cage’s work I want to wear his shoes. I feel like this is really being done at its best. And I want to bring that into my experience & I want it to be my own but I’m also happy walking in the steps. Stein said anything worth doing is worth doing again. So for me the challenge is to banish the heroes. To find my own thing.

Like these things are Rauschenberg.

And when I did this [Cover to Italo Calvino's The

Uses of Literature], I mean it’s this. I looked at this painting until I was mumbling it in my sleep. 1955. See the raw areas there? I’ve been looking at this painting for 20 years or so & with all the information it’s still raw. All that information. So sensual & then this other part is so noisy. I want to be able to instill that presence in my painting.

I was looking at this painting for so long & then I finally realized that instead of imitating it I would just steal the whole thing. And these Rauschenberg-like paintings, they didn’t begin consciously as Rauschenberg but as soon as I did them he was here with me.

M: Why do you want to banish them?

S: You don’t want to just be mouthing your father’s politics. You want to sublimate them. You want them to inform everything you are but you need your own version of the truth.

But I arrived at this Rauschenberg kind of painting from a different direction. Because I’m constantly involving myself in Picasso scholarship & I came across something some author said that to bring a collage into a piece brings a foreign edge into the plane. So the edge states its difference & its autonomy. That sounds rudimentary, silly even, but it’s so true. I mean here I am using a T-Square to create careful angles but why not bring in something from outside the painting, like these hanging things on the tapestry painting. They will automatically create its own edge.

M: But also by putting these old luggage tags on this, they look old, like something that was designed a long time ago & along with the tapestry it’s a use & mutilation of nostalgia.

S: Well, nothing can have one hermetically sealed association. It’s always a cascade of associations.

M: Right, the difference between a symbol & a sign is that a symbol has lost its multiplicity of associations.

S: These tags are actually from the sweatshop downstairs from my studio. They tag their laundry with these. When I got here I found them everywhere & I started collecting them. I didn’t know why exactly. It’s like how another painter might get into their new space & paint the space. Or another might say that paint the space & thereby own the space. So for me these tags are connecting to my space. And it looks like contemporary art, right? The work that has been most relevant for the last twenty years, installation & such, I don’t do those types of things. Sometimes my work looks like a dinosaur as compared to the new, which has very little to do with paint on a canvas. So I put these tags on the painting & it was like bing! Looking at the work I’m mired in & reading about the edge, I found these tags fit that.

And I’m not harping on this to be a Luddite, but the tapestry & the antique sensibility of it gives me pleasure because it looks like art to me. This older sensibility, the weft & the warp & things actually woven into it—it’s not on the surface it is the surface. So there’s bringing those in, a number of levels of bringing things in antique sensibility & the quoting the granddaddy, Rauschenberg. And there’s a sentimental quality of those tapestries. To me it brings all those signs in & loads them in.

And then I can’t be entirely object about it, but this to me looks like my painting. It is derivative, but the spirit & desires of this are all me. When I work against the heroes I think about how I can make a work more my own. How can I step away & leave my voice there. He’s still there.

But there’s a huge accumulation of people who bring me to this, maybe Twombly, Saul Steinberg, Guston. I can see them in my paintings. It is a confluence of things—much of it has to do with much older sensibilities. In the raw white spaces & the scatological lines & the drawings in my work I see Twombly.

Sometimes the direct quote is a way around the presence of the heroes. To just pull something from another painting. Could be Carravaggio, maybe you just want the foot. The foot that got the painting turned down by the church. That’s the foot I want.

Picasso used to do that to his contemporaries, people wouldn’t let him into their studios. Literarily turn him away. He was a cannibal, eating their children. So who better to steal from than a thief.

I was really insulted when I first read what Norman Mailer said in his book. Insulted because Picasso’s work to me was a critical bridge to the past. Mailer, in his own barrel-chested way, wrote that if Picasso had died in 1906 then he would have been remembered as a minor symbolist who would had done "Les Saltimbanques". And that painting blows my mind.

M: But it’s impossible to see that painting without all the future of Picasso sitting on it.

S: Right & that’s what he meant too. At the time I read that I thought he was underplaying it. Mailer is like Picasso in that he had to destroy things that cam before him. Any giant he had to either line up with they had to come down. Picasso was the same way. And Picasso made himself as an accumulation of several people. His situation was kind of like getting to New York City in the 60s & being a local hero from somewhere else, so you try to do Jackson Pollack or something, but meanwhile Pop Art has put that rest. Picasso was ten or twenty years behind, doing symbolism & he was embarrassed by that. Because he needed to be modern & so he tapped into the so-called negro art & sculpture & that sets him apart. He put himself together, like I can take this, this & this & become this. He could do that. Woody Allen looked at comics in his day & literally said a pinch of this & a pinch of that & then becomes strikingly original, or seemed like it.

From my point of view it’s a quest to get them to leave, to get them out of here. You’re always welcome, but get out.

M: Putting images onto a canvas is different than poetry, in that your materials are non-pragmatic. Poetry uses language, which everybody uses every day. However weird a poet is, they are still doing the same kind of act that a guy buying a bucket of chicken at a take-out window is doing. A painter has to teach themselves these techniques that are specific to the work, consciously learn a new thing. Does that factor into how you think of influence as a painter?

S: Painting is first a mimetic activity. I want to paint things. I need to copy them onto a surface. So immediately, you’re in the process of bringing over. It’s hard if you’re someone like myself who could be perfectly satisfied studying art history, just being in the books & looking. I have too much nervous energy to do that.

See that copy of Morandi, the bottle? When I started painting Mexican soda bottles I whipped out that Morandi. Now that painting is a flagship for other things to fall in line of mine & it helped me depart from what I was doing. With more command come more choices. As the hand becomes more controlled it becomes more willing. And the issue then is to decide where it will end up. I try so hard just to look at things.